At the Johns Hopkins University, the da Vinci robotic surgical system has been the star of medical robotics research on autonomous surgery and surgical training for years. Now, research teams led by Peter Kazanzides, a research professor in the Department of Computer Science and the Laboratory for Computational Sensing and Robotics, or LCSR, are making major advances to the system to help bring innovative techniques in robotic surgery research to reality.

They presented their work at the International Symposium on Medical Robotics in May.

The original da Vinci Research Kit (dVRK) has become dated compared to the systems that surgeons are using now—and there aren’t enough first-generation systems available for new researchers to use in their work, says Kazanzides.

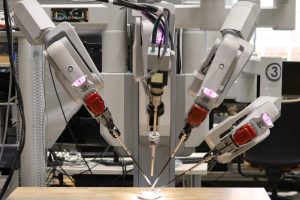

To solve this problem, his team—including CS PhD student Keshuai Xu; Jie Ying Wu, Engr ’21 (PhD); and Anton Deguet, an associate research engineer—developed an open-source version of the research kit called “dVRK-Si,” which supports the second- and third-generations of the system.

“We worked with Intuitive, the developers of the da Vinci, to figure out a solution that is able to reuse as much of their original system as possible while still protecting their proprietary information,” says Kazanzides. “This required the development of custom electronics, firmware, and software, but we’re now pleased to release this new research platform, which is more similar to systems in actual clinical use, to the greater surgical robotics community.”

The team’s current system primarily supports the da Vinci’s patient cart, which holds the camera and instruments that the surgeon controls from the console, but the researchers hope to continue working with the original da Vinci developers to add support for the surgical console itself.

In the meantime, Kazanzides and a team including CS PhD students Juan Antonio Barragan and Hisashi Ishida and alumni Yu-Chun Ku, Engr ’24 (MSE), Jingkai Guo, Engr ’18 (PhD), and Junxiang Wang, Engr ’23, ’24 (MSE), have made a first step toward solving the problem of communication loss during remote robotic surgery, or telesurgery, in new work.

Telesurgery has the potential to solve a major problem: the low number of expert surgeons in many countries. It can also reduce travel costs for both patients and medical professionals, while also allowing for easier sharing of knowledge and training techniques.

But rural areas and battlefields are often subject to intermittent periods of communication loss, much like “dead zones” in cellular service—but far more dangerous in the case of remote surgery.

When signal loss occurs, the surgical robot in the field stops in its tracks. Currently, the human surgeon on the other end must wait until the signal is reestablished. Instead, Kazanzides and team propose the use of a digital twin that simulates the remote robot’s hardware in real time, allowing the surgeon to command a virtual robot until the real one can catch up when communication is restored.

“A key benefit of this strategy is eliminating disruptions in the user’s workflow, as they can seamlessly transition to a virtual environment with the confidence that the system will catch up to them after the communication is restored,” explains Kazanzides. “Moreover, this method guarantees that the robot will follow all of the user’s intended motions and never has to select actions on its own, which could pose a safety risk.”

To this end, the researchers constructed a digital twin of the da Vinci surgical system and developed a method that logs all the moves a user makes during a period of communication loss; these changes are then replayed at double speed once the remote connection is reestablished.

The team conducted a user study to evaluate the efficacy of their proposed system as opposed to simply freezing the robot in place, asking engineering students to use this “replay method” to remotely move objects between pegs on a pegboard during a communication loss. The students experienced less frustration and completed the pegboard task 23% faster when using their new method, the researchers report.

However, they note that their current approach assumes a static, unchanging environment, which is not the case for most surgeries. As such, their next step is to experiment with more realistic environments, requiring an accurate simulation of the entire surgical environment—a challenge the team is eager to take on.

“We also encourage collaborative effort from the larger research community to explore different input devices, communication imperfections, and control strategies to overcome poor communication channels,” says Kazanzides. “This way, telesurgery can see broader and safer applications around the world.”

See their research in action below: