As robots become more integrated into our daily lives, it’s vital that researchers design robots capable of making social connections with human users.

Researchers in the Johns Hopkins University’s Intuitive Computing Laboratory, directed by John C. Malone Assistant Professor of Computer Science Chien-Ming Huang, presented their latest work on social robots at the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction held earlier this month in Melbourne, Australia. From generating robotic small talk to curating appropriate facial expressions, they hope their findings can aid manufacturers in creating robots that people want to work with.

“See you later, alligator”

In many countries, small talk plays a crucial role in building trust, rapport, and social bonds in the workplace. In fact, researchers have found that people who work with robots often express a desire for this kind of social interaction, wishing they could chit-chat with their robot coworkers like they do with their human peers. But how do you make small talk with the robotic arm working next to you on the assembly line?

Supported by the National Science Foundation, Huang, CS PhD student Kaitlynn T. Pineda, and third-year undergraduate Ethan Brown sought to find out by conducting a study in which they programmed a functional, non-humanoid robot to make small talk with its human teammates.

The research team compared 58 participants’ interactions with a robot arm that only made on-task comments versus one that also engaged in small talk while completing a simple assembly task. Although some participants thought the robot asked too many conversational questions and felt that they themselves responded only out of social obligation, those who interacted with the talkative robot generally reported having better rapport with the machine, with over half of the participants still conversing with it well after the task was finished.

Some even went as far as saying a proper goodbye to the robot: “There was a participant who used the expression, ‘See you later, alligator,'” Pineda recalls. “And of course, the robot responded, ‘In a while, crocodile.’”

While participants engaged with and generally appreciated the robot’s attempts at small talk, the researchers note that these kinds of interactions raise ethical concerns, such as inviting the potential for deception by unintentionally encouraging users to think of robots as empathetic or intelligent. That’s why the team calls for future research to examine the long-term effects of robotic small talk on human-robot collaboration and to explore how it can be integrated into real-world settings safely.

“As robots become more integrated into workplaces and assistive environments, designing them to consider the human need for social connection could improve collaboration, engagement, and overall user experience,” Pineda says. “Our findings show that even without a humanlike appearance, robotic systems can foster rapport through small talk, suggesting avenues for improving teamwork in industries that utilize human-robot cooperation, such as manufacturing and health care.”

It’s more than an expression

A key facet of human connection, facial expressions have also been shown to influence human-robot interaction: When done right, they increase users’ perceptions of likability, companionship, and trustworthiness and sense of collaboration. But current methods for generating robotic facial expressions are labor-intensive, lacking in adaptability, and limited in emotional range, leading to repetitive behaviors that actually reduce the quality of their interactions.

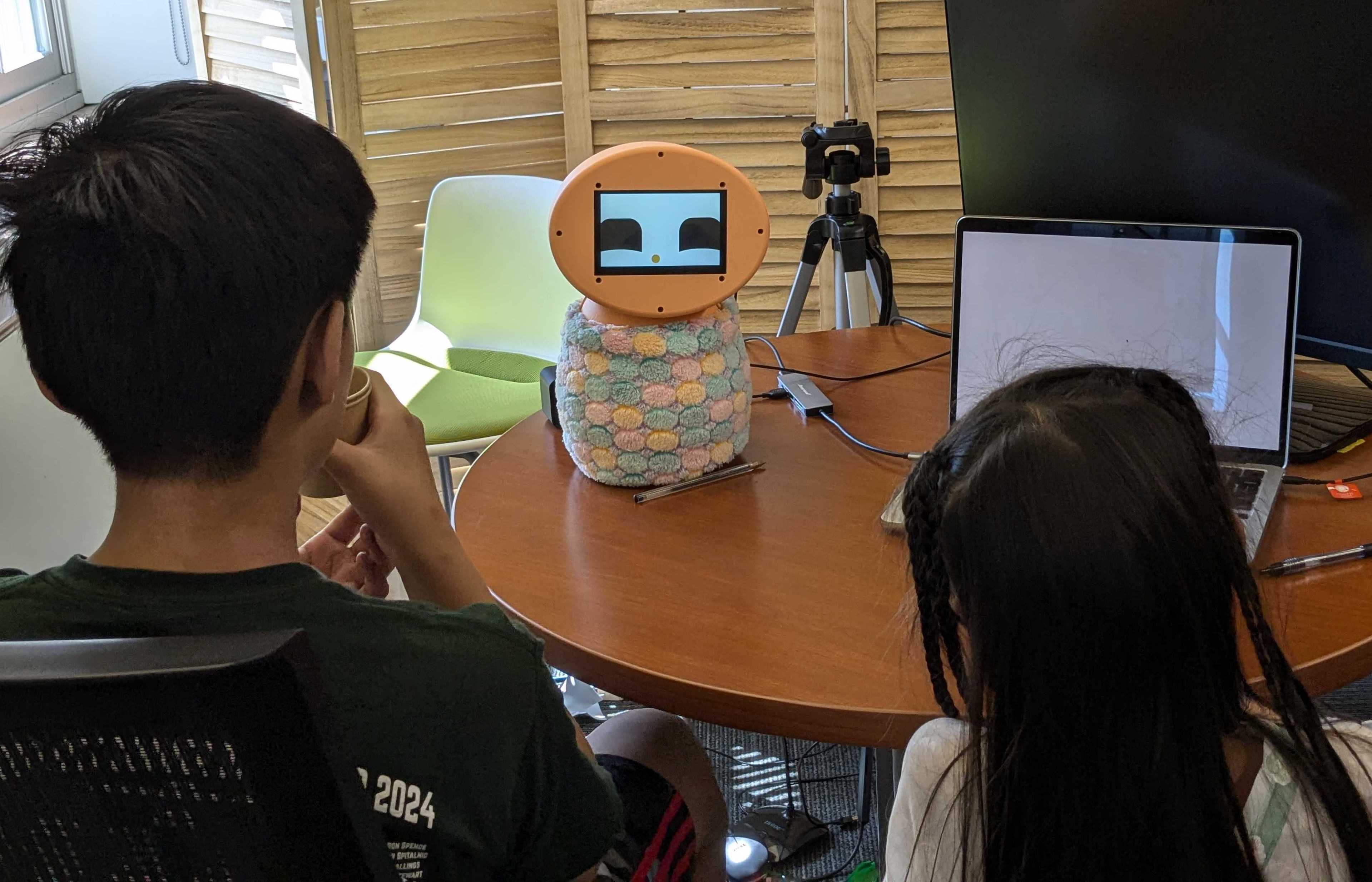

That’s why CS PhD students Victor Nikhil Antony and Maia Stiber have created a new, open-source system that uses language models to generate better robotic facial expressions than traditional methods. Called Xpress, the system’s core innovation is a three-phase process that analyzes robot dialogue and user speech, socio-emotional context, and previous conversation history to create color-coded facial expressions that are both contextually and emotionally appropriate.

The researchers tested Xpress on a custom robot in two user studies—one focused on storytelling and the other on natural conversation. In both, the team evaluated the generated expressions on how context-aware, expressive, and dynamic they were in interactions with real users.

Image Credit: Intuitive Computing Laboratory

Adult participants generally found the facial expressions to align well with the story they were told, frequently commenting on the diversity and range of expressions, while child participants expressed a high level of enjoyment in their interactions with the robot, reflected by their willingness to sit still and listen to additional stories.

For the conversational study, the researchers simplified the facial expressions so they could be generated in real time as users spoke with the robot. Participants still felt that these expressions were appropriate, but ran into more issues with their timing and intensity.

Only using language models to generate facial expressions could result in inappropriate or even harmful robot behaviors due to the bias present in the models’ training data, so Huang’s team proposes giving stakeholders like educators and caregivers the option to “co-create” content and robot behaviors suited to their specific needs.

“Additionally, co-created behaviors can in turn inform and condition language model outputs, achieving auto-generated behaviors that better align with user safety and social norms,” the researchers write.

The team plans to explore more types of body language and speech features, such as intonation and tempo, to further enhance Xpress’ ability to understand socio-emotional context and generate more nuanced behavior.

“Overall, Xpress is a step towards enabling organic, unscripted, and contextually fluid human-robot interaction experiences,” says Antony. “It brings us closer to more relatable robots by helping shift people’s perceptions of them and helping build robots that people feel more comfortable with—that feel closer to us.”